When we talk about the experience of eating spicy food, we often describe it as a taste, but scientifically speaking, that burning sensation on your tongue isn’t a taste at all. In fact, what we perceive as "spiciness" is actually a form of pain—a clever evolutionary trick played by certain plants, and mediated by a compound called capsaicin.

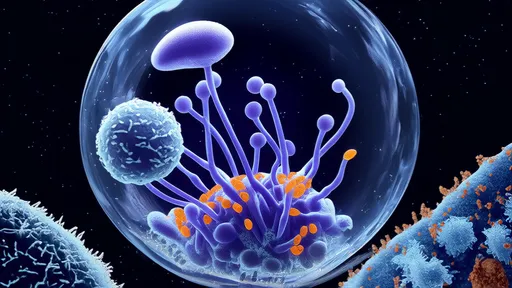

To understand why spiciness isn’t a taste, it helps to first clarify what taste actually is. The human tongue recognizes five basic tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter, and umami. These are detected by taste receptors—specialized cells that send signals to the brain about the chemical composition of food. Spiciness, however, doesn’t fit into this category. Instead of engaging taste receptors, capsaicin—the active component in chili peppers—binds to pain receptors known as TRPV1 receptors.

These TRPV1 receptors are normally activated by high temperatures, alerting the body to potential burns or tissue damage. When capsaicin comes into contact with these receptors, it tricks them into sending the same alarm signals to the brain, even though no actual thermal damage is occurring. That’s why eating a habanero pepper can feel like swallowing fire—your nervous system is literally being fooled into thinking your mouth is on fire.

This biological mechanism explains why the sensation of spice is so universal and intense. It isn’t about flavor in the traditional sense; it’s about sensation, and specifically, the sensation of pain. And while pain might sound negative, humans have learned not only to tolerate this sensation but to enjoy it. The thrill of eating spicy food comes from the body’s reaction—the endorphin rush that follows the initial shock, a natural painkiller response that can produce feelings of euphoria.

Interestingly, not all cultures experience or use spiciness in the same way. In some parts of the world, like Mexico, India, or Thailand, spicy food is a cornerstone of the culinary tradition. The use of chili peppers and other spices isn’t just about heat; it’s about depth, complexity, and even social and cultural identity. The ability to handle high levels of spiciness is often worn as a badge of honor, a testament to one’s toughness or familiarity with the cuisine.

But why would any plant evolve to cause pain in the animals that eat it? From an evolutionary perspective, it’s a defense mechanism. Capsaicin deters mammals from consuming the peppers, as mammals have the TRPV1 receptors and would tend to avoid the burning sensation. Birds, on the other hand, don’t have these receptors and can eat peppers without any discomfort, thereby helping to spread the seeds over wider areas. It’s a fascinating example of coevolution—where the plant develops a trait to favor one type of consumer over another.

For humans, the relationship with capsaicin is love-hate. Some people can’t get enough of it, while others avoid it entirely. This variation isn’t just cultural; it’s also physiological. Regular consumption of spicy food can actually desensitize TRPV1 receptors over time, meaning that avid spice lovers may need increasingly higher doses to achieve the same level of heat. It’s a form of tolerance, not unlike building a tolerance to certain drugs or stimuli.

Moreover, the experience of eating something spicy isn’t limited to the mouth. Capsaicin can activate pain receptors all along the digestive tract, which is why some people experience discomfort or even sweating long after the meal is over. In extreme cases, it can cause gastrointestinal issues, though for most people, the body adapts without serious problems.

Beyond the immediate sensation, capsaicin has been studied for its potential health benefits. It has anti-inflammatory properties, may boost metabolism, and is even used in topical pain relief creams for conditions like arthritis. However, these benefits come with caveats, and overconsumption can lead to adverse effects, especially for those with sensitive systems.

So the next time you take a bite of a spicy curry or a jalapeño popper, remember: you’re not tasting something—you’re feeling something. That burn is your body’s way of saying, "Warning: heat detected!" even if there’s no real fire. It’s a sensory illusion, one that humans have embraced, celebrated, and integrated into countless dishes around the world.

In the end, the story of capsaicin is a story of perception, adaptation, and even a little mischief—both on the part of the plant and the people who eat it. It challenges our understanding of taste and reminds us that eating is a multisensory experience, where pain and pleasure often intertwine in the most delicious ways.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025