There is perhaps no greater disappointment in the frozen dessert world than scooping into a container of premium ice cream, anticipating a luxuriously smooth and creamy experience, only to be met with a gritty, icy, and crystalline texture. That unpleasant sandiness on the tongue is the work of ice crystals, the arch-nemesis of ice cream perfection. For artisanal producers and home churners alike, the quest for ultimate smoothness is a scientific and artistic pursuit, a battle fought on the fronts of recipe formulation and churning technique. Understanding the enemy—the formation and growth of these ice crystals—is the first step to victory.

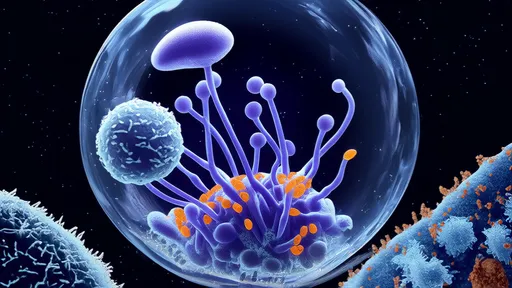

The foundation of ice cream is a complex colloidal system comprised of ice crystals, air bubbles, fat globules, and a highly concentrated sugar solution. The size and quantity of the ice crystals within this matrix are the primary determinants of texture. When we perceive smoothness, what we are actually sensing is the absence of large, detectable crystals. The human tongue can detect ice crystals larger than about 50 micrometers. Below this threshold, the sensation is one of pure, unadulterated creaminess. The goal, therefore, is not to eliminate crystals entirely—an impossibility—but to create a multitude of crystals so infinitesimally small that they are imperceptible.

Ice crystal formation is a dynamic process that begins the moment the base mix hits the cold walls of the churning machine. It starts with nucleation, where water molecules organize around a tiny impurity or speck of dust, forming the seed of a crystal. During the aggressive freezing and churning process, countless these nuclei are formed. The subsequent fate of these nuclei—whether they grow into large, jagged crystals or remain small and well-dispersed—is where the art and science of ice cream making truly comes into play. The journey to a flawless texture is a race against time and physics, managed through a combination of intelligent ingredient selection and precise mechanical action.

The recipe, or formulation, of the ice cream base is the first line of defense against iciness. It is a carefully calculated balance of components each playing a specific role in controlling water and modulating crystal growth. Fat, primarily from dairy sources like cream and milk, is a crucial textural agent. Fat globules act as physical barriers within the mix, obstructing the free movement of water molecules and thus impeding their ability to join and enlarge existing ice crystals. A higher butterfat content, often between 14% and 18% in premium ice creams, provides a richer mouthfeel and contributes significantly to a smoother consistency by creating a more obstructive network for crystal growth.

Perhaps the most potent weapon in the formulator's arsenal is sugar, but its role is multifaceted and goes far beyond mere sweetness. Sugar molecules dissolve in the water portion of the mix, forming a syrup. This syrup has a lower freezing point than pure water. The higher the concentration of dissolved sugars, the lower the temperature at which the water will freeze. This means that even as the temperature in the churn drops below the freezing point of water, a significant amount of the water remains unfrozen, trapped in a super-cooled syrupy state. This liquid portion, known as the serum, surrounds the tiny ice crystals, making it more difficult for them to collide and merge. This phenomenon, known as freeze-point depression, is critical for maintaining a soft, scoopable texture straight from the freezer.

Other solids, such as milk proteins and stabilizers, play supporting but vital roles. Milk proteins help emulsify the fat and water, creating a more stable and uniform structure. Stabilizers like guar gum, locust bean gum, or xanthan gum are hydrocolloids that bind with water molecules, effectively making the water itself thicker. This increased viscosity physically hinders the mobility of water molecules, dramatically reducing the rate at which they can migrate to the surface of an existing crystal and cause it to grow. While often maligned in ingredient lists, used judiciously, stabilizers are powerful tools for promoting minuscule crystal size and preventing coarse crystallization during storage.

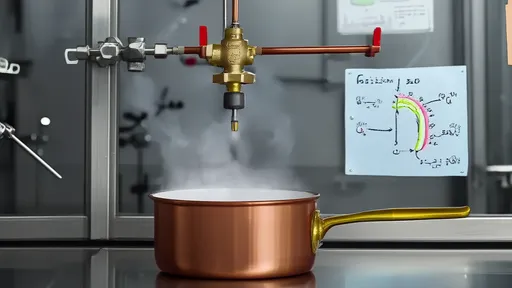

However, a perfect recipe is only half of the equation. Without the correct mechanical action, even the most brilliantly formulated base can succumb to a crystalline fate. This is where the churning process, specifically agitation, becomes paramount. The primary function of churning is twofold: to incorporate air (overrun) and to simultaneously freeze the mix while constantly agitating it. This constant agitation is the engine of smoothness. As the mix freezes on the chilled walls of the barrel, the dasher immediately scrapes it off, breaking up these nascent ice formations into tiny shards and distributing them evenly throughout the unfrozen base.

This process is effectively a cycle of microscopic fracturing and redistribution. Without agitation, a solid block of ice would form on the sides. With agitation, you create a vast number of small seed crystals instead of a few large ones. The continuous movement also ensures that the cold is transferred evenly throughout the entire volume, promoting uniform nucleation. The speed of the churn matters; too slow, and the scraping is inefficient, allowing crystals to grow too large before being dislodged. Too fast, and you can incorporate too much air or cause excessive butterfat clumping (which leads to a greasy mouthfeel), all while potentially not providing enough time for sufficient heat exchange. The ideal churn finds a balance that maximizes crystal disruption while optimally freezing and aerating the mix.

The final, and often overlooked, phase of crystal management occurs after the churning is complete: hardening. As the soft, freshly churned ice cream is rapidly cooled to deep-freeze temperatures, the remaining water in the unfrozen serum continues to freeze. The speed of this process is critical. A slow temperature drop provides ample time for water molecules to migrate to existing crystals, causing them to grow larger. This is known as Ostwald ripening, where large crystals grow at the expense of small ones. Rapid hardening, achieved with a powerful blast freezer that can bring the product down to its final storage temperature as quickly as possible, locks the crystal structure in place, preserving the delicate, small-crystal architecture achieved during churning.

Temperature fluctuations during storage are the silent killer of texture. Every time the freezer door is opened or the temperature cycles, a small amount of the ice cream melts. When it refreezes, it does so slowly and statically, without the benefit of agitation. This water refreezes onto the surface of existing crystals, causing them to grow progressively larger over time. This is why an ice cream that was once perfectly smooth can become icy after weeks in a home freezer. Consistent, ultra-cold storage is essential for maintaining textural integrity from the first scoop to the last.

The pursuit of the perfectly smooth scoop is a testament to the fact that great ice cream is more than the sum of its parts. It is an intricate dance between chemistry and physics, between ingredient and action. It requires a deep understanding of how milk fats coat the palate, how sugar syrups resist freezing, and how gums manage water. It demands precision in mechanical force and thermal transfer. When a master formulator and a perfectly calibrated churn work in concert, the result is a frozen dessert so sublimely smooth, so devoid of any crystalline distraction, that it transcends the category of mere treat and becomes a textural masterpiece. The magic lies not in the absence of ice, but in its masterful, imperceptible distribution.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025