In the heart of every kitchen, where steam hisses and aromas mingle, lies a humble yet profound piece of engineering: the pressure cooker. To the uninitiated, it might seem like just another pot with a tightly sealed lid, but to those who understand the physics at play, it is a vessel of transformation, where the very laws of nature are harnessed to achieve culinary perfection. At the core of this magic is a simple but powerful principle: by increasing pressure, we can raise the boiling point of water, and in doing so, unlock flavors, textures, and efficiencies that are otherwise impossible. This is not mere kitchen trickery; it is science in action, a dance of molecules and forces that has revolutionized cooking across cultures and centuries.

The story begins with water, that most essential of substances, and its behavior when heat is applied. Under normal atmospheric conditions, at sea level, water boils at 100 degrees Celsius (212 degrees Fahrenheit). This is a fact we learn early in life, but few pause to consider why it happens or what boiling truly represents. Boiling occurs when the vapor pressure of the liquid equals the atmospheric pressure pressing down upon it. At this point, bubbles of water vapor can form within the liquid, rise, and escape into the air. It is a dynamic equilibrium, a balance between the energy of the water molecules and the weight of the air above. But what if we change that pressure? What if we alter the very environment in which the water exists?

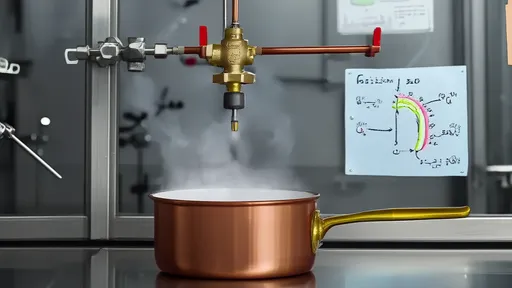

Enter the pressure cooker, a sealed container designed to trap steam and build up pressure inside. As heat is applied, water turns to vapor, but with nowhere to go, it accumulates, increasing the internal pressure. This is where the physics becomes fascinating. According to the principles of thermodynamics, specifically the relationship described by the Clausius-Clapeyron equation, the boiling point of a liquid is dependent on the surrounding pressure. Increase the pressure, and you increase the boiling point. It is a direct, predictable relationship: for every increase in pressure, the temperature at which water boils rises accordingly.

Inside a typical pressure cooker, pressures can reach up to 15 pounds per square inch (psi) above atmospheric pressure. This might not sound like much, but its effect is dramatic. At this pressure, the boiling point of water jumps from 100 degrees Celsius to around 121 degrees Celsius (250 degrees Fahrenheit). That extra 21 degrees might seem modest, but in the world of cooking, it is a game-changer. Foods that would normally take hours to soften or cook through can be ready in a fraction of the time. Tough cuts of meat become tender, legumes soften without pre-soaking, and vegetables retain their nutrients and vibrant colors because the cooking time is reduced. The higher temperature also means that reactions like the Maillard browning—responsible for deep, complex flavors—occur more readily, enhancing the taste of dishes in ways that slow cooking cannot match.

But how does this pressure build-up actually happen? It starts with a tight seal. The lid of a pressure cooker is equipped with a gasket that prevents steam from escaping. As the liquid inside heats up, vapor forms, and since it is confined, the number of molecules in the gaseous state increases. These molecules collide with the walls of the cooker and with the surface of the liquid, exerting force—pressure. The more heat applied, the more vapor is produced, and the higher the pressure rises. To prevent accidents, pressure cookers are fitted with safety valves and regulators that release excess steam if the pressure exceeds safe limits. This ensures that the cooker operates within a controlled range, harnessing the power of pressure without risking explosion.

The implications of this process extend far beyond the kitchen. In fact, the same principle is used in industrial settings, such as in autoclaves for sterilization, where high-pressure steam at temperatures above the normal boiling point ensures that medical instruments are free of pathogens. It is also employed in chemical engineering processes where reactions need to be accelerated or conducted at higher temperatures without using excessive energy. The pressure cooker is a miniature version of these technologies, a testament to how understanding basic physics can lead to practical innovations that improve daily life.

Yet, for all its scientific sophistication, the pressure cooker remains accessible and intuitive to use. Modern designs have made them safer and more user-friendly, with features like locking lids, pressure indicators, and multiple safety mechanisms. They are embraced by home cooks and professional chefs alike, not just for their speed, but for their ability to produce superior results. Imagine a stew that typically simmers for three hours; in a pressure cooker, it might be done in 45 minutes, with meat that falls apart at the touch and broth that is rich and deeply infused with flavor. Or consider grains like brown rice or barley, which can be perfectly cooked in minutes rather than half an hour, retaining a pleasant chewiness without being mushy.

There is also an energy efficiency aspect that cannot be overlooked. Because cooking times are shorter, less energy is consumed. In a world increasingly concerned with sustainability, the pressure cooker offers a way to reduce our carbon footprint one meal at a time. It uses less electricity or gas than conventional methods, making it not only a time-saver but an eco-friendly choice. This efficiency is particularly valuable in regions where fuel is scarce or expensive, and where traditional slow cooking methods are impractical.

But let us return to the science, for it is worth delving deeper into why pressure affects boiling point. Water molecules are held together by hydrogen bonds, which require energy to break. When heat is applied, molecules gain kinetic energy, moving faster until some have enough energy to escape the liquid phase and become gas. Atmospheric pressure acts like a blanket, pushing down on the surface and making it harder for molecules to escape. At higher altitudes, where atmospheric pressure is lower, water boils at a lower temperature because less energy is needed to overcome the reduced pressure. Conversely, in a pressure cooker, the increased pressure means molecules need more energy—higher temperature—to break free. This is why water can remain liquid at temperatures well above 100 degrees Celsius under pressure.

The history of the pressure cooker is itself a tale of innovation. First invented in the 17th century by Denis Papin, a French physicist, it was initially called the "steam digester" and was intended as a tool for scientific experiments. Papin understood that steam under pressure could achieve high temperatures, and he used it to study the properties of materials. It was not until the 20th century that the pressure cooker became a household appliance, popularized for its ability to save time and money. Today, it has evolved into multi-functional devices like electric pressure cookers, which combine the principles of pressure cooking with modern technology for precise control and convenience.

In conclusion, the pressure cooker is a brilliant application of physics, transforming the way we cook by manipulating pressure and temperature. It demonstrates how a fundamental understanding of natural laws can lead to inventions that enhance our lives in mundane yet profound ways. By raising the boiling point of water, it unlocks efficiency, flavor, and nutrition, making it a staple in kitchens around the world. So the next time you hear the gentle hiss of a pressure cooker, remember: it is not just steam escaping; it is the sound of science at work, turning simple ingredients into extraordinary meals.

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025

By /Aug 29, 2025